ASM’s eight game unbeaten run came to an end at the hands of PSG, a run which can be largely attributed to Monaco’s effective high-press. Did Sunday’s loss expose weaknesses within this system?

The peak of Monaco’s pressing powers were evident during the comprehensive 3-1 victory away to Angers at the beginning of the month, prompting Nico Kovac to announce, “This is the way in which I want to see my team evolve.”

Since then, the characteristics of Kovac’s pressing ideology have become ever-more pronounced, with clearly identifiable pressing triggers, traps and patterns. Kovac, a proponent of an intense pressing philosophy, advocates for a strong press, understanding the potential rewards involved in winning the ball in the opponent’s third.

The intensity of the press itself has been facilitated by a tactical shift, which now sees Monaco utilizing a 4-2-3-1, as opposed to the 3-4-3, a formation which, for now at least, has seemingly exhausted its usefulness in Kovac’s eyes. The switch is now allowing more effective, coherent pressing patterns, and forcing sides into traps.

Sunday’s defeat in the French capital, some argued, highlighted deficiencies within Monaco’s high press. The problem, however, may not lie within the system itself, but can be attributed to a myriad of game-specific issues including line-up choice and the world-class talent at PSG’s disposal.

Firstly, it is worth identifying the characteristics that have contributed to the success of Kovac’s press, to identify how, if at all, it differed at the Parc des Princes.

Man-to-man marking

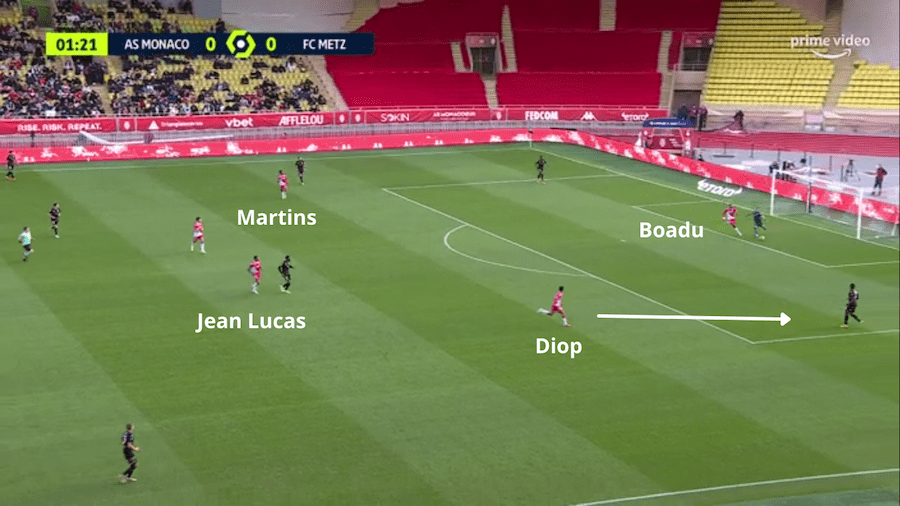

A clearly distinguishable element of Kovac’s press is the man-to-man approach. Whenever the ball goes back to the opposition’s goalkeeper, the Monaco midfield pushes up, going man-to-man with the opposition midfield, whilst the wingers close down the defenders. The striker in the system will energetically hunt down the goalkeeper to rush him into a split-second decision.

This example from the Metz match, which ultimately leads to Sofiane Diop opening the scoring, demonstrates this system. The goalkeeper, without a short option will, more often than not, be forced into playing the ball long, which is unlikely to stick, or elicits an error from the goalkeeper. Either way, the ball is gifted back to Monaco, allowing them to regain possession and control the game.

In this circumstance, the keeper punted the ball long, but Aurélien Tchoumaméni, who was pushed high, just in-front of his opposite number, nipped in, intercepted and advanced the ball. The press is therefore acting not solely as a defensive tool, but also as a means of starting attacks in dangerous areas when the opposition haven’t had an opportunity to reset.

A pass back to the goalkeeper therefore represents a pressing trigger, which signals for the Monaco press to adopt a man-to-man press, therefore decreasing the opposition’s progressive passing options.

Pressing triggers and traps

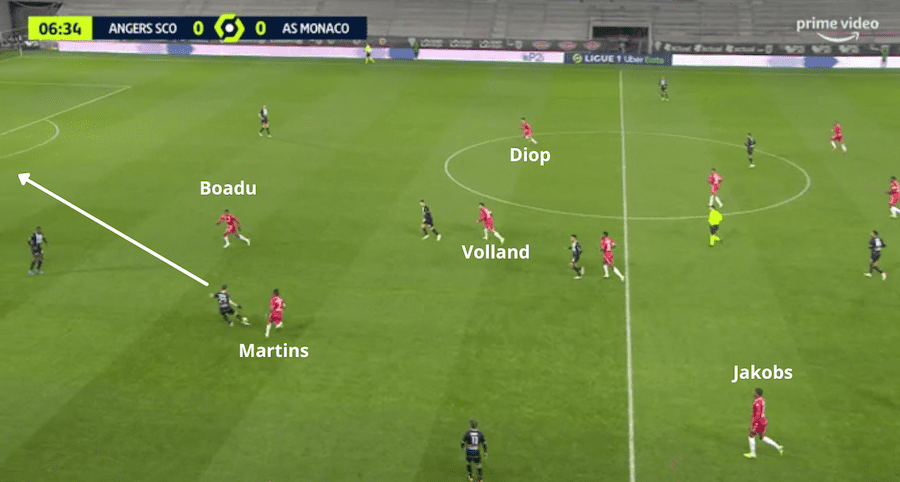

From early-on against Angers in particular, Monaco’s pressing triggers were very clear. This is, of course, largely thanks to the system implemented by Kovac, but tantamount to the philosophy itself is the on-pitch implementation from the players. Gelson Martins and Myron Boadu were very impressive, their game intelligence and recognition of certain triggers allowed Monaco to shepherd the opposition into undesirable positions.

The sixth minute of this game provided a perfect snapshot of Monaco’s attacking system, displaying its multiple components. Monaco’s press meant that Angers’ were frequently forced to utilise the wing-backs as a means of ball progression. Monaco caught the wing-backs in a pressing trap; as the ball came out to them, the Monaco wing-back, in this instance Ismail Jakobs, pushed up, using the right sideline as an extra defender and preventing Angers from progressing the ball through that flank.

Angers subsequently had to play back, which was then the trigger for Martins to put pressure on the ball, whilst Boadu, rather cleverly, was primed to put pressure on the other centre-back option, whilst also keeping the Angers left-back in his block-shadow – leaving the goalkeeper as the only available option.

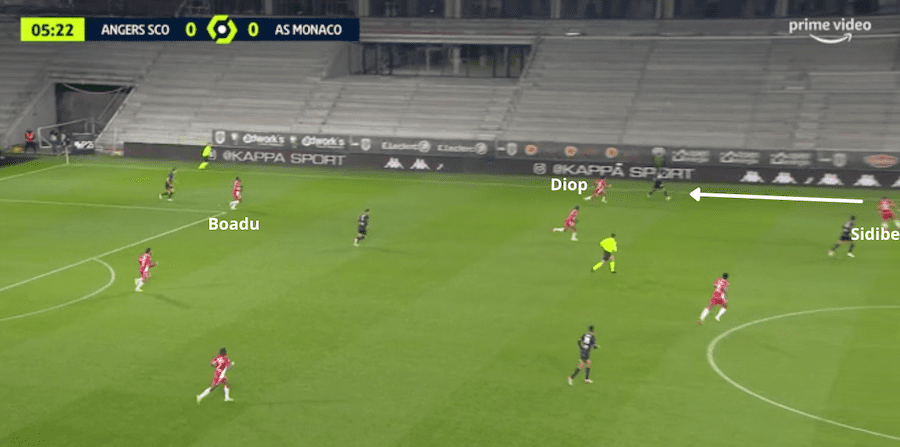

As the ball was recycled back to the goalkeeper, the Monaco press shifted across to the left, this time it was the job of Diop to apply pressure to the man on the ball. Notably, Diop, just like Martins, curves his run, blocking off the progressive ball into the defensive midfielder. It is clearly something that Kovac has drilled into his attacking players, and that they, in turn, have taken on-board and executed perfectly.

Deprived of any other options, Angers played it into the opposite wing-back, and just as Jakobs prevented progression on the other flank, Djibril Sidibé did the same. As the ball was released, the trap was sprung and Sidibé advanced rapidly to close down the man on the ball, forcing him into an error.

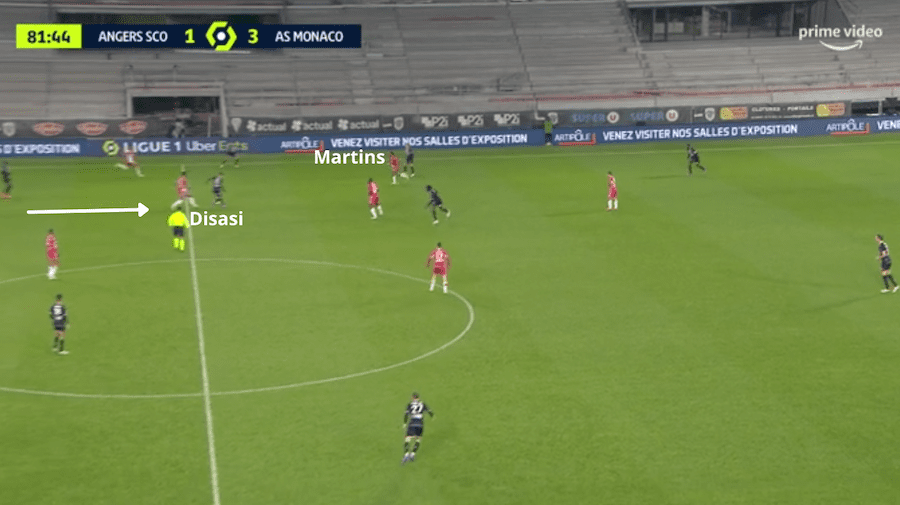

On the rare occasion that Angers could progress the ball into the midfield, that was then a trigger for the centre-backs to step-up and put pressure on the ball. In this instance it is captain Axel Disasi, who as soon as the ball was played, stepped up and succeeded in dispossessing the Angers player.

Condensing the space

All of these triggers and traps, which were meticulously executed, were extremely efficient at dispelling any attacking threat from the opposition. However, the success of Kovac’s press is two-fold, not only snuffing out threats, but also priming his side for an attack. As the Monaco press is so compact, and the space is compressed, it means that once the ball is recovered it can then be quickly advanced with a variety of short, progressive passing options.

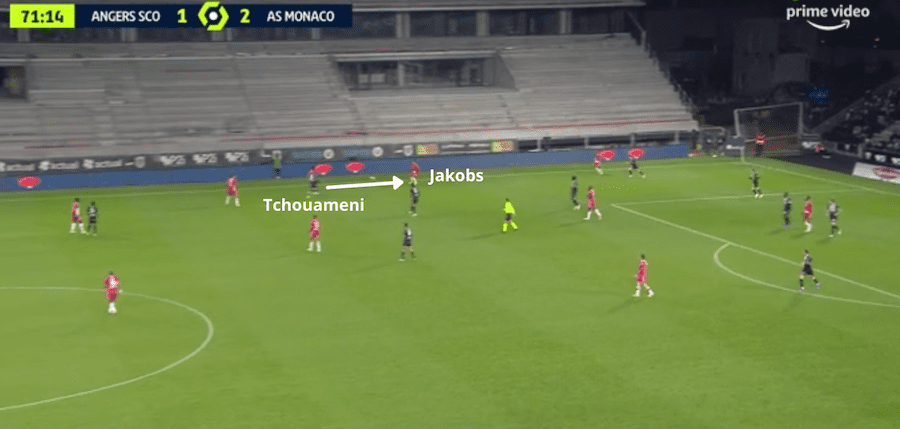

In this instance, the Angers player receives the ball near the corner flag, with a man-to-man and zonal pressing approach, Monaco eradicate the progressive options, forcing the player into attempting a long ball. Tchouaméni, who is pressing high, then cuts it out, and due to the compactness of the Monaco unit, the French international midfielder can head it down to Jakobs, who is only a couple of yards away. Jakobs then advances the ball with a short dribble before being fouled. Disasi then scores from the resulting free-kick.

AS Monaco’s high press therefore has allowed them to control games by limiting the opposition’s options to advance through the phases, forcing long balls, which often gifts possession back to the Principality side.

On other occasions, the press is an attacking tool, allowing Monaco to win the ball high-up, whilst the opposition are still in an offensive shape. The compactness of the press not only allows man-to-man marking, but also allows players to adopt a zonal press, which keeps opposition players in block shadows, and therefore cuts off passing channels. The compactness then allows Monaco to advance the ball quickly, by offloading to a nearby teammate.

Pressing against PSG

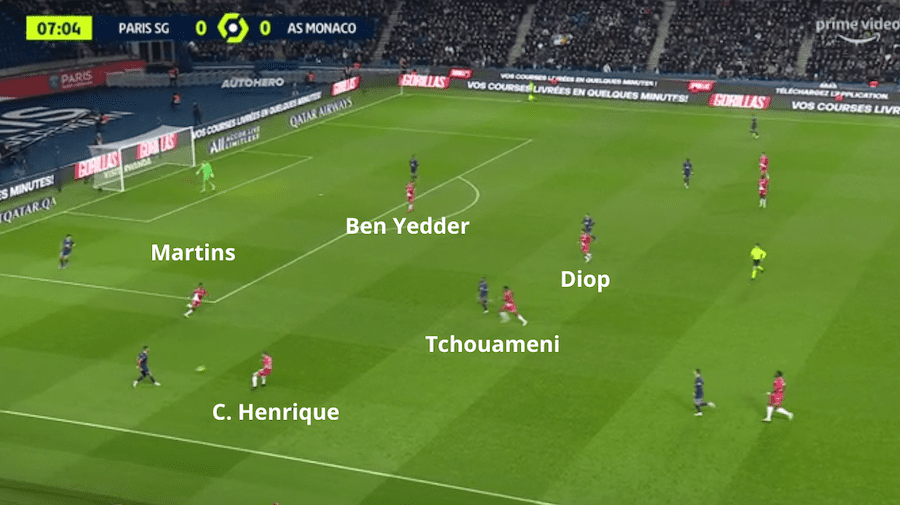

Monaco, thanks in part to their pressing, dominated possession in the first-half, but found themselves two goals down thanks to two individual errors. The same pressing triggers were evident. Notably, as soon as the PSG wing-backs received the ball, Monaco condensed the space, midfielders and wing-backs pushed up, and they used the sideline as an extra defender. In the instance below, Tchouaméni, manages to nip in and win the ball as the ball is shepherded into a player under pressure. It also triggered Caio Henrique to push up and apply pressure, just as Ismail Jakobs and Djibril Sidibé did against Angers.

What was lacking on Sunday, however, was the intensity and consistency of the press. Too often Marco Verratti, a world-class, press resistant midfielder, was allowed too much time on the ball to turn and pick a progressive pass, which allowed PSG to bypass the press.

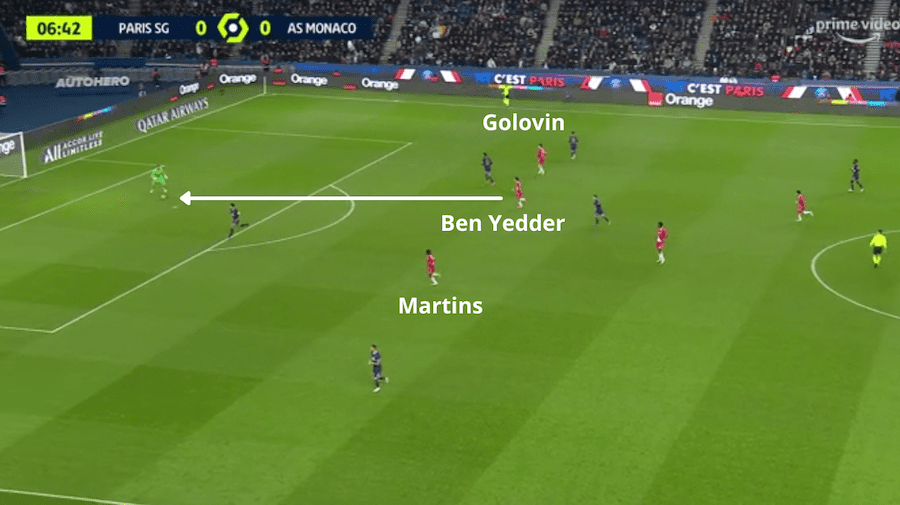

The lack of intensity of the press, particularly from Wissam Ben Yedder, meant that PSG weren’t forced into making rushed, suboptimal decisions, and coupled with the world-class talent at PSG’s disposal, this was always going to be a recipe for disaster.

Before the PSG fixture, Kovac was critical of Ben Yedder’s work in the high-press, stating, “I am waiting for him to defend”. Statistically, Ben Yedder fares much worse in his pressing stats compared to his team-mates, as is demonstrated below:

This was also visually evident during the PSG match. In contrast to Boadu, who hassled and harried the Metz and Angers goalkeepers throughout his time on the pitch, Ben Yedder afforded the PSG goalkeeper ample time, allowing him to pick out a pass, whilst preventing Monaco from effectively shepherding the ball into pressing traps.

Monaco’s application of Kovac’s press therefore didn’t differ greatly from previous, more successful fixtures. The difference instead lay in the quality of PSG’s players in being able to break the press, as well as a lack of intensity brought about by the manager’s line-up choices.

Ben Yedder, a truly world-class striker, therefore represents a bit of a conundrum for Kovac. Although, ideally, he would like to fit him into his starting 11, his inability to carry out the manager’s pressing instructions may well make him more of a hindrance than a help in Monaco’s bid to reach the European places.

Analysis: ASM’s high-press and the Ben Yedder conundrum