France woke on Saturday to its coldest morning in over a decade, with temperatures plunging to -22°C in the Jura mountains and numerous cities recording double-digit negative temperatures as a polar air mass from the Arctic blankets the entire country.

The commune of Les Fourgs in Doubs, in the heart of the Jura mountains on the French-Swiss border, recorded the nation’s coldest temperature at -22°C on Saturday morning. In the plains, severe frosts saw temperatures drop to -11.8°C in Aurillac, -9.5°C in Annecy, -9°C in Orléans, -8.9°C in Brive-la-Gaillarde, -8.6°C in Cognac and -8.2°C in Le Mans.

Monaco, whilst spared the extreme cold hitting eastern France, is experiencing its coldest sustained period since the “Beast from the East” brought snow to Nice in February 2018. Temperatures across the Côte d’Azur have dropped 12-15°C below seasonal averages, with Monaco’s forecast showing maximum temperatures struggling to reach 10-11°C and overnight lows of 2-5°C through mid-January.

For a principality accustomed to mild Mediterranean winters where temperatures typically range from 8-13°C and rarely drop below 4°C, the prolonged cold represents an unusual shock to residents and the region’s famed outdoor lifestyle.

The frigid conditions arrive exactly 317 years after the most catastrophic winter in European recorded history began—a freeze so severe it killed hundreds of thousands and reshaped the continent.

5th January 1709: When Europe froze solid

On 5th January 1709, Europe’s coldest winter in 500 years crept in overnight. The chill stretched from England to Russia, and this time there would be no quick thaw.

Whole trees froze and shattered. Trade came to a standstill as snow made roads impassable. The Thames River and the Baltic Sea froze solid. Copenhagen Harbour reported 27 inches of ice. Flocks of birds froze mid-air and fell from the sky. Temperatures plummeted to -21°C.

This was long before weather forecasting, so people had no warning. The Great Frost—as it came to be known—would reshape the continent for a generation.

France was hardest hit. At least 600,000 people died from cold, famine and disease that year alone. The government formed a commission to manage grain distribution as prices rose sixfold in some places. Punishments for hoarding grain were severe—up to and including execution.

Wine froze solid in barrels. Bread turned so hard it had to be cut with an axe. Livestock died in frozen fields. Fish died beneath frozen rivers and lakes. Wheat crops failed across the continent. Agriculture collapsed. Each loss compounded the famine to come.

Some residents adapted creatively, moving provisions by cart via newly formed ice routes and burning furniture for warmth. In Venice, people used ice skates to navigate the frozen canal network. But for many, adaptations weren’t enough.

The cold disrupted two wars. The War of the Spanish Succession stalled completely. The Great Northern War—Russia versus Sweden—ended in defeat for the weakened Swedish army, helping vault Russia to world-power status and redrawing the political map of Europe.

When the continent finally thawed in spring, flooding devastated low-lying areas. All that meltwater had to go somewhere, and the ground was frozen more than three feet down, unable to absorb the deluge.

What caused the Great Frost?

Climatologists are still debating the exact cause. Some blame volcanic eruptions in preceding years, which may have created a dust veil high in the atmosphere that blocked the sun. Others cite an extended period of low solar activity—the weakest in millennia—that coincided with the freeze.

What’s certain is that the atmospheric patterns that winter created a scenario similar to what meteorologists are seeing now: a fundamental disruption forcing Arctic air far south of its usual range.

2026: A disrupted Polar Vortex

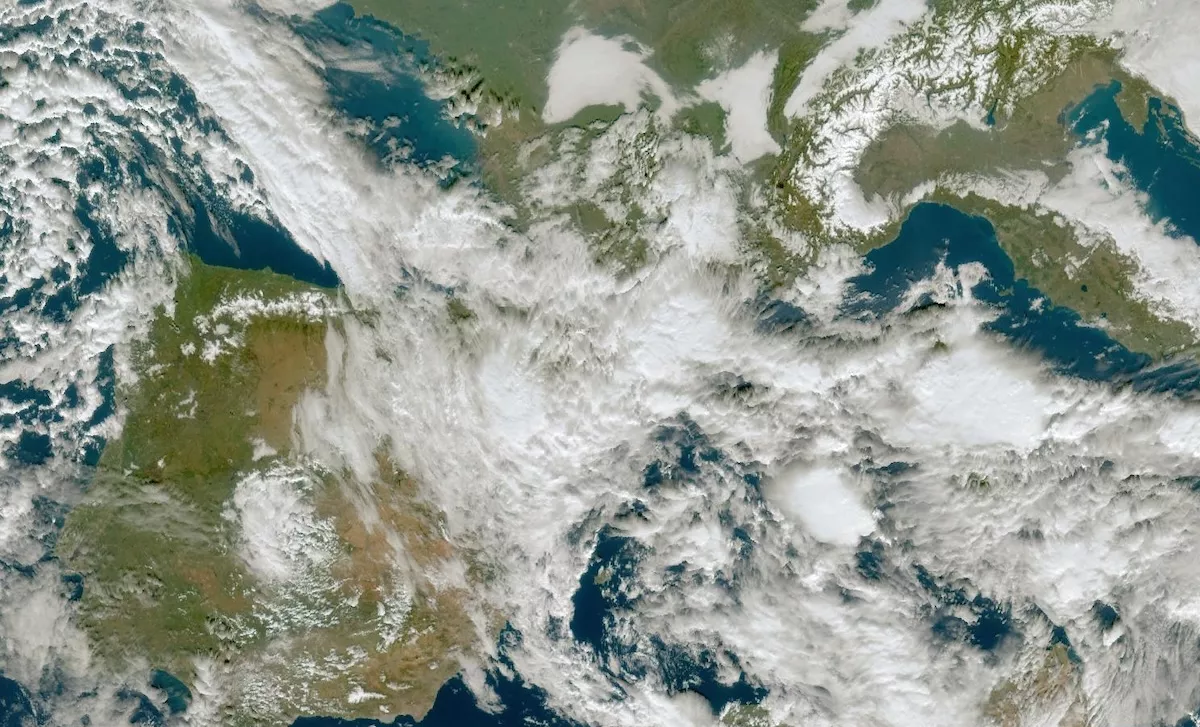

The current cold snap, whilst incomparable to 1709’s catastrophe, shares a similar meteorological trigger. The Polar Vortex—an enormous ring of powerful winds circulating around the North Pole at 20-50km altitude—has been severely disrupted by a stratospheric warming event.

When strong, the vortex traps cold air in polar regions. When disrupted, that air escapes into mid-latitudes.

“This expansive ridge of high pressure acts as a meteorological dam, forcing a deep reservoir of Arctic air to spill southward across Europe,” meteorologist Marko Korosec explained. “The result is a sustained disruption of the Polar Vortex, setting the stage for an extended period of winter weather dominance across the continent.”

Temperatures across France are currently 10 degrees below seasonal norms for early January, with the polar air mass extending as far south as North Africa. Weather models show potential snowfall in higher terrain in northern Algeria.

As frigid Arctic air collides with the Mediterranean Sea’s lingering warmth and high moisture content, it’s triggering intense storms. Forecasters term these “Balkan snow bombs”—powerful Mediterranean cyclones bringing deep snow accumulations and whiteout blizzards across southeastern Europe.

Cold weather history

The region has weathered cold snaps before, though nothing approaching 1709’s severity or even the current conditions in eastern France. The most extreme modern winter struck in 1985, when temperatures plunged to -11°C in Hyères, -12°C in Cannes, and a record 38cm of snow fell on Nice.

The early 2012 European cold wave buried the Mediterranean coast in deep snow by late January, with Corsica receiving 40cm. Most recently, the February 2018 Beast from the East brought snow to Nice for the first time in six years.

Stay updated with Monaco Life: sign up for our free newsletter, catch our podcast on Spotify, and follow us across Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and Tik Tok.

Photo source: Meteo France