In less than a year as director, Cecilia Bartoli has brought a new impetus and energy to the Opéra de Monte-Carlo, with an exciting production programme and top of the line performers, plus the added stardom that this celebrated Italian coloratura mezzo-soprano brings to the stage.

Cecilia Bartoli was born in Rome, Italy. Her father is a dramatic tenor and her mother lyric soprano, and both were members of the Rome Opera chorus. They recognised Cecilia’s capabilities and were the inspiration for her to start singing as a teenager, with her mother remaining as her only voice teacher.

Her professional career started at age 19 when she performed on a television show with baritone Leo Nucci. She impressed conductors Herbert von Karajan and Daniel Barenboim, who recognised her talent and voice suited perfectly to the difficult coloratura repertoire of Mozart and Rossini.

The rest is history, as Bartoli has become one of classical music’s most popular performers, selling millions of albums and filling up concert halls. The popularity of her projects has enabled her to reevaluate and rediscover long lost operas and composers, reviving a forgotten repertoire, and putting the spotlight on new singers and new pieces.

Her new lyric roles, her concert programmes and albums are welcome with enthusiasm all over the world.

Bartoli is now an intrinsic part of the celebrated history of the legendary Opéra de Monte-Carlo.

Monaco Life: How did you come to be appointed director of the Opéra de Monte-Carlo?

Cecilia Bartoli: I grew into this profession slowly, not out of any ambition to become “the boss”. I have simply been passionate about large scope projects for more than 25 years, and they became increasingly more intricate.

It started with my recording projects dedicated to little-known composers, concert tours, documentaries, staged performances, exhibitions, a novel and more. I even asked friends to contribute something from their own field of activity.

When I became artistic director of the Salzburg Whitsun Festival in 2012, I was entrusted with a mini festival of four intense days highlighting a particular theme each year. New art styles, such as ballet and cinema, featured here from the beginning. Now, in Monte-Carlo, I have the great honour and pleasure to create an entire season where my ideas materialise.

As an accomplished singer and director, you have a rich network of worldwide renowned artists. So, do you plan to bring la crème de la crème to the Principality?

Absolutely! I want to bring people to Monte-Carlo who have not been here before, or very rarely, such as Jonas Kaufmann or Lang Lang. I plan to bring back artists such as the mythical Placido Domingo, with whom I experienced a memorable emotional moment singing together in the Salle Garnier in April 2023.

What makes a successful opera director?

First and foremost, you should have a clear vision, be open, creative and passionate about the arts in general, that you then will transmit onto your audience, to make them feel as excited as you are. For that, you must get to know and connect with your public.

It is imperative to gain the trust of your teams to motivate them. I am most grateful for my Monte-Carlo team, which is small but extremely professional and dedicated, and most important we share a common spirit.

It is true that you are only as strong as your team. How do you challenge each other?

I think that most artists hate routine. You need to show them new repertoire and different approaches to well-known pieces, you need to create a professional, efficient, cooperative, but also pleasant working environment. It is especially important to listen to each other’s ideas and needs.

A successful theatre production is always the result of teamwork, paired with a professional attitude, commitment to the cause and respect for the work of art you are producing.

How do you influence the staging for the operas you present?

I would like to think that I do not influence, but I try to anticipate certain results by choosing the leading team carefully. My job is to be available and help or mediate if any questions arise, or if I am asked for advice.

It is well known that opera has held a prominent place in the art world for 400 years, but it is essential to prove relevance in the world we live in. What is the relevance of opera in our time and place?

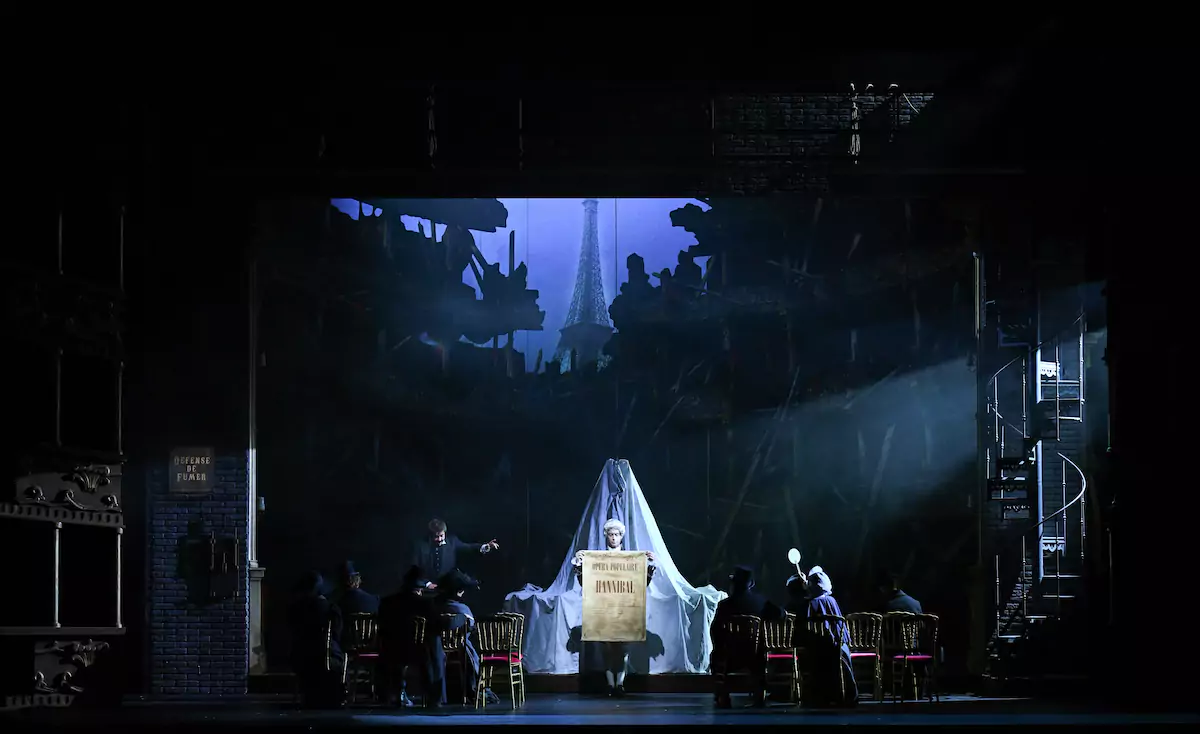

Opera is multifaceted, but also one of the most difficult art forms because it is so complex: you need singers, an orchestra, often a chorus, sometimes dancers. The libretto is often in a high foreign language literature and needs to be brought across to your listeners. You have the visual side – costumes, lights, and sets – which the spoilt 21st audience expects to be at least as stunning as in a Harry Potter movie or video game.

Opera will always be relevant as it covers all aspects of our lives, from birth to death, love and hatred, politics and philosophy, private interest and public duties, rural and city life, princes and paupers, entertainment, excitement and consolation, comedy, tragedy and farce – in summary, everything for every taste and interest. Opera has survived for centuries, and it will continue do to so, if we prove it is significant, and we present it at the highest possible standard, with the greatest passion and respect for our audiences.

What is the importance of storytelling as the basis of a good opera?

If you mean story telling as a theatrical means – the way an opera unfolds before the audience – it is essential. We must keep the attention of the public even after the curtain falls. Besides, it is difficult to generalise about opera – it being a genre that emerged in the 17th century. There are operas with a great story, there are others without a story. There are operas with a weak story, but fantastic music. But there are no good operas with a great story but bad music.

What is your view in making music scores changes?

Many questions in theatre are resolved according to practical considerations. And a gripping performance only works if certain rules of the theatre are respected, coups de-théâtre, for example. If you succeed in improving a theatrical effect by making small changes to the score, then it is admissible in my mind. Throughout the 18th, 19th and early 20th century, composers changed elements in their scores according to the conditions of a particular house or an individual musician or the abilities of a singer. Particularly in the 18th century, entire arias and scenes were revised to suit a particular cast, so it is nothing unusual really.

It is well known that you encourage the development of young artists, and you are already working with both the Princess Grace Dance Academy and the Rainier III Music Academy, indicating that you favour crosspollination with other art forms. Would you collaborate with Pavillon Bosio, directed by talented scenographer Thierry Leviez?

Monaco is extremely rich in cultural initiatives and institutions! I find it very inspiring to discover them and find ways to work together. As we speak, the singers of our new Opera Academy – dedicated this time to French music – are being integrated in Jean-Christophe Maillot’s new ballet production of L’Enfant et les Sortilèges, a fantastic new project.

Apart from the institutions you mention, we also collaborate with our decade-long partner, the Philharmonic Orchestra of Monte-Carlo and – for the first time – Le Printemps des Arts for the evening with John Malkovich’s ‘Their Master’s Voice’.

The Pavillon Bosio is a fascinating institution, and I could very well imagine finding a common ground for future projects.

What is your vision for the future of opera?

This art genre has survived for centuries and gone through profound changes in society and the world at large. If it is performed well, it will survive, maybe in different shapes and forms; the repertoire will surely change, as it always has done. For certain it will remain alive with the help of you all!

Join the Monaco Life community – the largest English media in the Principality.

Sign up for the Monaco Life newsletter, and follow us on Facebook, Instagram , LinkedIn and Tik Tok.

Main photo of Cecilia Bartoli, photo credit: Marco Borrelli