In early March, Cory Trépanier excitedly attended the opening in Monaco of his Into The Arctic exhibition of paintings and films. Just days later, he flew back home to Canada, the Oceanographic Museum near empty amid a looming coronavirus lockdown.

The exhibition still hangs on the walls of the museum, but its doors remain closed to the public. It is unlikely that anyone in Monaco will get a chance to lay eyes on Cory’s exhibition before it is packed up and shipped off to North America in May.

So, Monaco Life is taking you on a virtual tour of Into The Arctic, with your own personal guide and Q&A with the artist.

In every canvas that he creates, Cory Trépanier has been face-to-face with some of our planet’s greatest natural wonders.

His Into The Arctic exhibition tour, featuring more than 50 oil paintings and three films, has been making its way across the world since 2017.

This March, it was Monaco’s turn to host the exhibition at the Oceanographic Museum as part of Monaco Ocean Week.

The title piece in the collection is the 15-foot wide ‘Great Glacier’, one of the largest Arctic landscape paintings in Canada’s history.

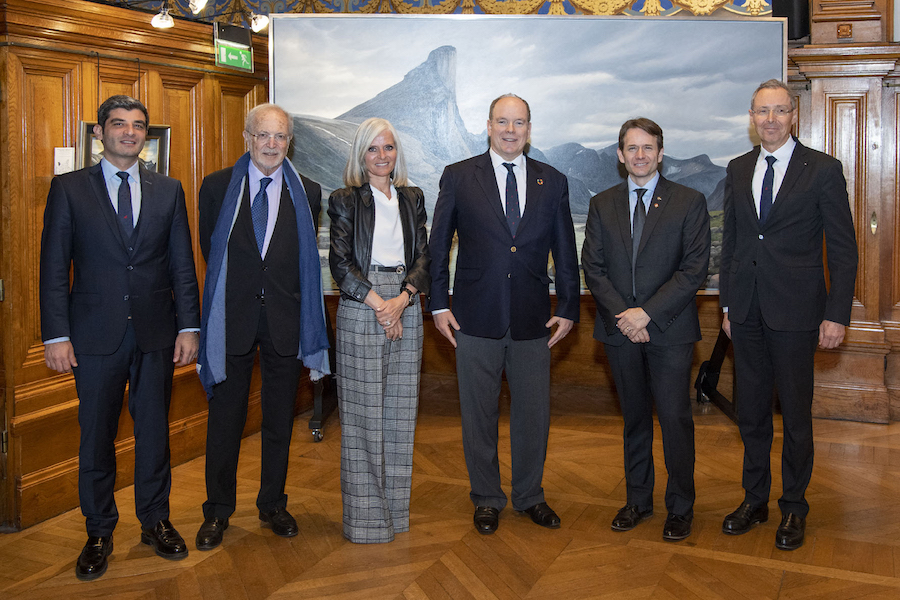

It caught the eye of Prince Albert when he was taken on a private tour of the exhibition during its opening.

Little did Cory know that Prince Albert would be among the last people to admire his paintings in the Principality – most of which are on loan from private collectors exclusively for this tour.

Monaco Life: What was it like meeting with Prince Albert, someone who is so publicly passionate about saving our planet?

Cory Trépanier: I first met Prince Albert during the first public screening of my latest ‘Into the Arctic’ film – the last in a trilogy of Arctic documentaries – hosted by the Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation during Monaco Ocean Week in 2018.

On Wednesday 4th March, I had the opportunity to meet with the Prince once again, taking him on a private tour of the collection. We connected on different topics of the environment and his recent dive to the deepest depths of the Mediterranean Sea, where he sadly saw garbage bags on the sea floor.

It was wonderful to see how engaged the Prince was with Canada’s North, and with my canvases and films born from this remote and fragile part of our planet. And it was an opportunity to personally thank him for writing the thoughtful foreword to my forthcoming coffee table book, Into the Arctic: Paintings of Canada’s changing North. The visit was an experience that I will never forget, and one that I am very grateful for.

Were there any particular paintings that the Prince was drawn to in the collection?

You mean apart from the giant 15-foot wide ‘Great Glacier’? (laughing). The Prince had visited Frobisher Bay in Canada before with the Students on Ice programme, which his Foundation has been supporting for many years now. So, it was great for him to be able to look at a painting of a view that was familiar to him.

He also seemed to really enjoy the final film of my Arctic trilogy – Into the Arctic: Awakening, which is part of the exhibition, along with the first two. The documentary follows me in the Arctic for nine weeks and 25,000 kilometres; I travelled with Inuit elders, paddled the most northerly canoe route in North America, walked in the footsteps of early explorers John Rae and John Franklin, and connected with a changing land, to bring it to the eyes of those who may never see it.

The film was too long for him watch during our visit, so I organised to send him a Blu-Ray.

Your paintings are all snapshots of reality. Can you tell us about the process you go through to create landscape paintings like these?

I begin by looking at the map and dream about the places I want to explore. Then I research what is actually accessible – because one of the most difficult things about the Canadian Arctic is access. It is a million and a half square kilometres of archipelago; one does not just show up. Some of these expeditions took a year to organise with airlines, Arcticcommunities, Inuit outfitters, local hunters and trapper’s clubs – people who are invaluable to work with in polar bear country.

All of these experiences get me out there, and once I am there, it takes a few days for the world that I have known – the phones and the noise – to start melting away. It takes a whole shift in mentality to let go and be aware of the world around me so that I start moving in unison with nature. Often, I carry a very heavy pack – 120 pounds at one stage – with my painting gear, photography gear (because I take pictures for reference and sharing), film gear, and camping gear.

Then the plane flies away and I am out there on my own. I realise just how small and minute I am in this world and how humbling it is. If anything goes wrong, it is a major issue to get out, so I find myself watching my steps more closely, trying not to take undue risks.

The creative process itself begins with choosing an environment in which I can immerse myself completely, and only then do I feel I am in a position to even think about painting.

As I start to look around me, I see a lot of options, but the challenge is finding just the right scene that combines powerful composition, lighting and subject matter, and also connects deep inside on an emotional level. 99% of the time, over the course of a few hours, other things start to happen – light will pass, clouds will move through, the light will change. My heart starts to race a little faster. And that’s when just taking a quick photograph and leaving does not offer the deeper experience of connection that I seek as artist, so I set up my easel and start painting.

Given those challenges, how do you manage to complete a painting?

I carry a paint box that hold 10 panels – back-to-back in 5 slots – each covered in Belgian linen.

I set a panel up on my half-box French easel, and I start painting directly with my oils. After two to three hours I will end up with the essence of the scene. Sometimes those sessions go better than others; sometimes if I am getting eaten by mosquitos I may finish a little earlier. There’s a certain rush in the process of painting plein air, you are battling the conditions, it is an emotional high.

After a session, I sit back and soak it all in and ask myself if this captures some of what drew me here in the first place. I want to go beyond just representing a place to actually conveying the experience of being there: the awe felt, and the sense of wonder.

At home in the studio, I may take another week to finish a small piece, while a larger painting may take several months or more. Almost every painting in the museum right now has actually travelled from the Canadian Arctic itself.

Is it disappointing that the public were not able to really see your exhibition because of the lockdown?

Of course. But what an honour it has been to have my exhibition in Monaco. I am so pleased to be part of the message that is coming out of the Oceanographic Museum and from the Prince about the protection of the environment, our Poles and the Arctic, and the need to care for people who live up in these regions as well.

It is a great desire of mine that my work connects people to our planet in ways that they may not often see. I hope it draws others closer, inspires greater care for these places and deeper consideration of our individual and collective actions as a society.

It is fascinating to see how the environment across the globe is breathing a little easier during this crisis. I hope this inspires a vision of what the future can be like if societies move forward more sustainably after this pandemic passes.

You are isolated and largely alone on these expeditions, much like us all currently in confinement. What advice do you have for people who are self-isolating?

Keep busy. It is a great time for people to reach back to their childhoods and the hobbies they had growing up, or explore new ones. Be creative in some fashion. With tools as simple as paper and pencil you can explore a satisfying part of yourself that may have been long buried. Find ways to connect with nature. If you are fortunate to have family with you, relish this time with them.

These difficult times will pass. In the future, when we look back on it, wouldn’t it be wonderful to have a new skill, a new passion, and new stories developed through this turmoil, that can bring newfound joy for the rest of your life?