It is not too late to change the future of our planet if we speed up our measures to act and adapt, say the authors of a new IPCC report on climate change released Monday. We speak to one of the authors, Nathalie Hilmi at the Scientific Centre of Monaco.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released its latest large-scale report at midday on 28th February. Titled ‘Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability’, it is the second part of the Sixth Assessment Report and the IPCC’s first since November’s COP26 summit.

Nathalie Hilmi contributed to the 6th Assessment Report, mainly in chapter 18: ‘Climate resilient development pathways’, and the CCP4 on the Mediterranean region.

“This report shows that the scientific evidence is unequivocal, climate change is a threat to human wellbeing and the health of the planet. Any further delay in concerted global action will miss a brief and rapidly closing window to secure a liveable future,” Nathalie Hilmi told Monaco Life.

The report, for which the authors have analysed thousands of published scientific papers, shows that increased heatwaves, droughts and floods are already exceeding the tolerance thresholds of plants and animals, driving mass mortalities in species such as trees and corals. These weather extremes are occurring simultaneously, making the impacts increasingly difficult to manage. They have exposed 3.3 to 3.6 billion people to acute food and water insecurity, especially in Africa, Asia, Central and South America, on small Islands and in the Arctic.

The report says that, in order to avoid mounting loss of life, biodiversity and infrastructure, “ambitious, accelerated action is required to adapt to climate change, at the same time as making rapid, deep cuts in greenhouse gas emissions”.

The report finds that so far, progress is uneven, and there are increasing gaps between action taken and what is needed to deal with the increasing risks. These gaps are largest among lower-income populations.

“In the Paris Agreement, developed countries committed to mobilising $100 billion US a year to 2020 to reverse the climate change needs of developing countries, but this doesn’t cover all of the impacts that we are observing,” says Hilmi. “The estimated cost of adaptation for developing countries varies widely, but it is around $127 billion per year until 2030, and almost $300 billion US per year until 2050.”

It is a lot of money, acknowledges Hilmi – an economist specialising in macro-economics and international finance, “but if we don’t act now, the cost of inaction will be even higher in the future. And we must not forget the wider benefits such as saving lives, improving people’s health and preserving cultural identity, things that have no price.”

If humans can limit global warming to close to 1.5°C in the near-term, it would substantially reduce projected losses and damages in human systems and ecosystems, the report finds.

“The idea of climate resilient development is already challenging at the current warming levels, but it will become more limited if global warming exceeds 1.5°C, because in some regions, it will simply be impossible if global warming exceeds 2°C,” says Hilmi.

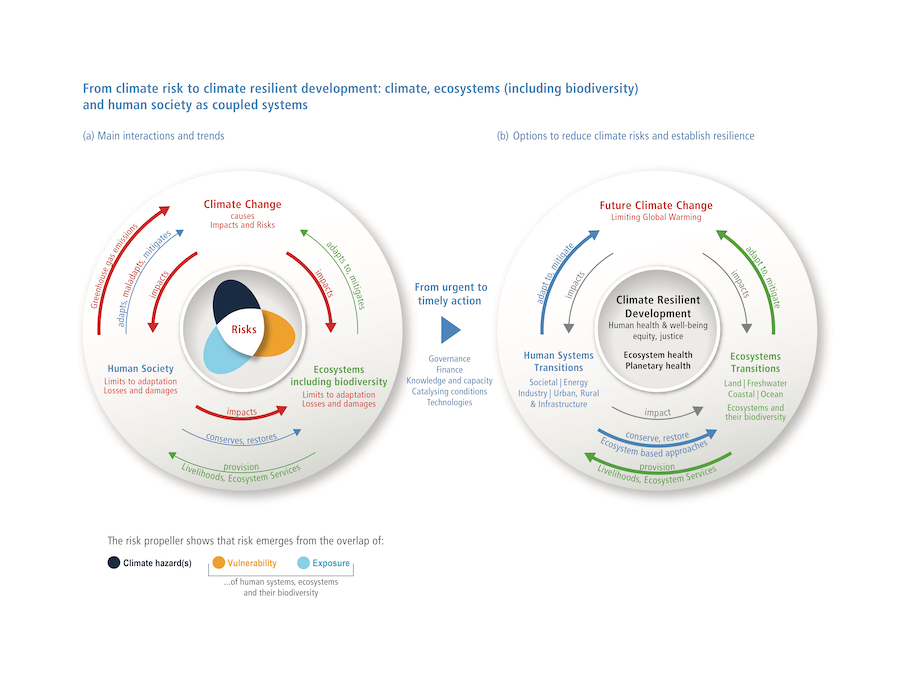

In her chapter, ‘Climate resilient development pathways’, Hilmi and a team of experts explore what can happen when governments, civil society and the private sector make development choices that prioritise risk reduction, equity and justice. International cooperation is needed, says Hilmi, as well as governments working at all levels with scientific and other institutions, media, investors, businesses, civil society, educational bodies, and communities – including ethnic minorities and Indigenous Peoples.

“Global change is a global threat, but actions can be local and individual,” says Hilmi reassuringly. “We need actions from international institutions and governments, but also from local decision makers and everyone in the civil society like you and me. We just have to transform our way of living. For example, our diets – eat less meat and it will have less impact on the environment, don’t let the water run unnecessarily when you wash your hands… these are small things that can be impactful on a global scale.”

The report also provides new insights into nature’s potential not only to reduce climate risks but also to improve people’s lives.

“This report is really interdisciplinary,” says Hilmi. “We have natural scientists and social scientists working together to examine the impact of climate change on nature and people around the globe. It shows that biodiversity loss and climate change are interlinked; that nature is capable of protecting the climate. When we have trees and our ocean is healthy, for example, they capture and store C02. If we conserve, restore or protect the mangroves, they will not only capture carbon, they will also filter the water for healthy fisheries and protect the coast from flooding and erosion. So, nature needs to be part of the solution.”

In order to maintain the resilience of biodiversity and ecosystems, the report states that 30% to 50% of Earth’s land, freshwater and ocean areas must be conserved.

In summary, Nathalie Hilmi says it is important to stay positive.

“It is not too late. But if we wait any longer, we will reduce our options of action.”

The new IPCC report will form part of discussions at the upcoming Monaco Ocean Week, a high-level summit organised by the Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation, as well as two United Nations events this year.

“I will be involved in several events for Monaco Ocean Week in which I will talk about the new IPCC report,” reveals Hilmi. “It will also be used for the UN Biodiversity Conference (COP15) in China in April, and the UN Climate Change Conference (COP 27) that will be held in Egypt in November.”

Photo by Nick Perez on Unsplash